The field of brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) has reached an exciting inflection point. Recent breakthroughs in invasive speech BCIs have achieved remarkable milestones—reported word-error rates below 5% and vocabularies exceeding 125,000 words. But these advances come with a fundamental limitation: they require brain surgery.

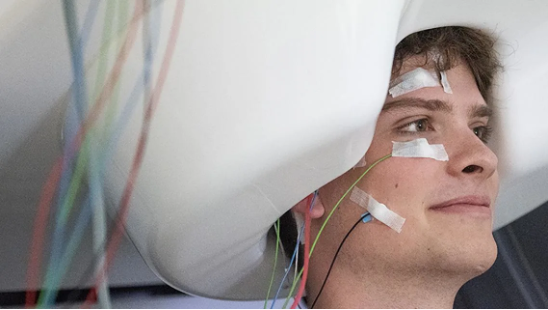

Part of the surgery to implant invasive electrodes into the brain (from Wikipedia)

What if we could achieve similar breakthroughs without surgical intervention? This is the driving vision behind the 2025 PNPL Competition, and we’re excited to share why we believe this competition represents a critical step towards that future.

The Ultimate Goal: Speech BCIs Without Surgery#

Our ultimate goal is clear: developing speech brain-computer interfaces that don’t require surgical implantation. The potential impact is profound—from restoring communication for individuals with paralysis or speech deficits like dysarthria, to enabling new forms of human-computer interaction that could benefit everyone.

However, non-invasive speech decoding faces significant challenges. While invasive BCIs leverage high signal-to-noise ratios from electrodes placed directly on or in the brain, non-invasive methods must contend with signals that are attenuated by the distance from brain and sensor. The gap between invasive and non-invasive performance has been substantial—most current non-invasive approaches show word-error rates approaching 100% (though see Jayalath et al.), whilst invasive systems report below 5%.

Addressing Field Limitations with LibriBrain#

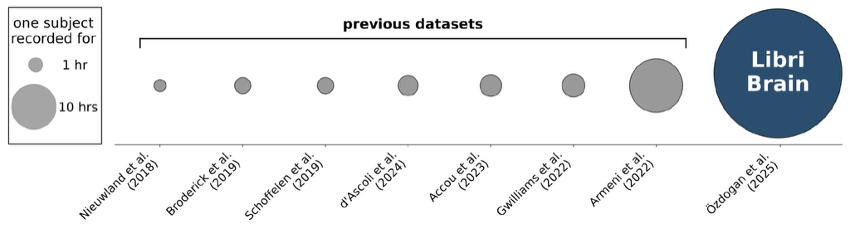

To tackle these challenges head-on, we’ve created LibriBrain: the largest within-subject MEG dataset recorded to date, containing over 50 hours of high-quality 306-channel neural recordings sampled at 250 Hz. This represents a 5× increase over the next largest dataset and 25-50× more data than typical MEG/EEG datasets.

Figure reproduced from Özdogan et al.

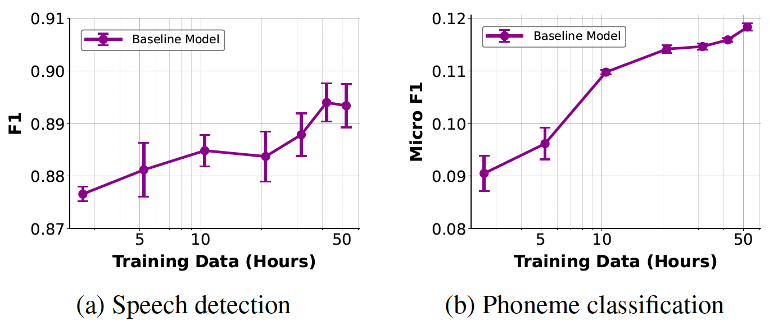

The dataset spans nearly the entire Sherlock Holmes canon across 7 books, recorded over 95 sessions from a single participant. This depth matters enormously—our baseline experiments demonstrate clear logarithmic scaling relationships between training data volume and decoding performance, consistent with scaling laws observed across machine learning domains.

Why does this matter? Empirical evidence shows that “deep data”—extensive recordings from the same individual—yields the largest gains in decoding performance. Previous datasets have been characterised as “broad but shallow,” including many participants but only 1-2 hours per person. LibriBrain flips this paradigm, providing the depth needed to train powerful AI models that can compete with surgical alternatives. That said, as we continue to grow the dataset, we also plan in future to release data from additional subjects.

Competition Design: Building Strong Foundations#

Why These Tasks?#

We’ve chosen two foundational tasks for this competition: Speech Detection and Phoneme Classification. Whilst our ultimate goal is brain-to-text decoding, recent attempts at full sentence decoding from non-invasive signals have yielded near-chance performance.

Instead of jumping directly to the hardest problem, we’re taking inspiration from the development of automatic speech recognition (ASR), which built strong foundations through phoneme-based approaches. Here’s why these tasks make sense:

Speech Detection provides a binary classification for every temporal sample (250 per second), making it our most accessible task—maximum data points with the smallest number of classes, compared for example to word or even phoneme events. This entry-level challenge mirrors the critical speech detection component used in the first invasive speech BCI for paralysed individuals.

Phoneme Classification offers several advantages over word-level tasks:

- No out-of-vocabulary problems: Unlike word classification, every phoneme in test data has been seen during training

- Better data efficiency: 1.5M phoneme examples across 39 classes versus 466k words across 16k+ classes

- Strong theoretical foundation: Phonemes are the building blocks of speech

Our baseline results show promising scaling behaviour which mirrors neural scaling laws observed across AI domains (e.g. Kaplan et al. and Antonello et al.). Both speech detection and phoneme classification performance improve logarithmically with the volume of training data:

Figure reproduced from Özdogan et al. (x-axes are log scale)

Why MEG?#

Magnetoencephalography (MEG) offers unique advantages that make it ideal for bridging the gap between invasive and practical non-invasive BCIs:

- Direct measurement of neural activity with millisecond temporal resolution

- Minimal signal distortion compared to EEG, as magnetic fields pass through tissue without degradation

- Spatial precision of 5-10mm routinely, with 2mm achieved in some studies

- No surgical risk, enabling safe data collection at unprecedented scale

Recent work by Défossez et al., d’Ascoli et al., and Jayalath et al. has demonstrated the potential of scaling non-invasive approaches with large datasets and modern AI methods. Whilst practical applications may eventually move towards more portable technologies like EEG, MEG provides the best current platform for proving that non-invasive speech decoding can compete with surgical alternatives.

Why Speech Comprehension?#

Our competition focuses on decoding speech comprehension (listening) rather than speech production. This design choice reflects both practical and strategic considerations:

Methodological advantages: Speech comprehension allows us to develop scalable AI methods with precise event timing. We know exactly when each phoneme occurs, enabling reliable model training and evaluation. Comprehension tasks further avoid muscle artifacts introduced by speech production (e.g. speaking aloud) which reduce signal quality and confound non-invasive decoding.

Alignment with literature: This approach aligns with recent successful non-invasive decoding work, including influential papers by Tang et al., Défossez et al., and our own recent advances in non-invasive brain-to-text (e.g. Jayalath et al. and Jayalath et al.) that show promise for generalising from comprehension to production tasks.

Stepping stone to production: Whilst we ultimately want to decode attempted speech or inner speech, comprehension provides a crucial intermediate step for developing and validating methods that can later generalise to production tasks. This approach is supported by evidence of overlap in the brain between speech comprehension and production representations (e.g. Hickok and Poeppel and Pulvermüller et al.), and by recent evidence that decoding models trained on listening data can transfer to inner speech tasks (e.g. Tang et al.).

Driving Innovation and Building Community#

This competition is designed to create an “ImageNet moment” for non-invasive neural decoding, inspired by how ImageNet revolutionised computer vision. We’re providing not just data, but a complete ecosystem designed around the foundational tasks we’ve established:

- Standardised evaluation metrics to enable fair comparisons

- Easy-to-use Python library (pnpl) with PyTorch integration, designed to be as accessible as CIFAR-10

- Two competition tracks: Standard (LibriBrain data only) and Extended (any training data)

- Tutorial materials that run in free Google Colab environments

- Active community support through Discord and dedicated resources

- Public leaderboards for real-time progress tracking

The dual-track structure ensures both algorithmic innovation (Standard track) and exploration of what’s possible with unlimited compute resources (Extended track). At least £10,000 in prizes will reward the most innovative approaches.

Looking Forward#

This is just the beginning. The hope is that the PNPL Competition will become an annual event, tackling a progression of increasingly challenging tasks as our datasets grow and our methods and insights improve. Think of it as a curriculum for the field—building from strong foundations towards the ultimate goal of robust, non-invasive speech BCIs.

We’ll be releasing a series of blog posts throughout the competition to dive deeper into technical aspects, share insights from the community, and highlight innovative approaches. Whether you’re a seasoned researcher or new to the field, we’ve designed this competition to be accessible and impactful.

The future of speech BCIs doesn’t have to require surgery—let’s work together to make this future a reality

Ready to participate? Visit the rest of our competition website to get started with tutorials, download the data, and join our community Discord. The competition is officially running from 1st June 2025 - 30 September 2025 and will culminate in a session at NeurIPS in December 2025. As a record of progress, we expect the submission system and leaderboards to continue running afterward.

Key References#

The 2025 PNPL Competition, reference models, and pnpl library:

Landau, G., Özdogan, M., Elvers, G., Mantegna, F., Somaiya, P., Jayalath, D., Kurth, L., Kwon, T., Shillingford, B., Farquhar, G., Jiang, M., Jerbi, K., Abdelhedi, H., Mantilla Ramos, Y., Gulcehre, C., Woolrich, M., Voets, N., & Parker Jones, O. (2025). The 2025 PNPL competition: Speech detection and phoneme classification in the LibriBrain dataset. NeurIPS Competition Track.

The LibriBrain dataset:

Özdogan, M., Landau, G., Elvers, G., Jayalath, D., Somaiya, P., Mantegna, F., Woolrich, M., & Parker Jones, O. (2025). LibriBrain: Over 50 hours of within-subject MEG to improve speech decoding methods at scale. arXiv preprint.

Other recommended reading:

Défossez, A., Caucheteux, C., Rapin, J., Kabeli, O., & King, J. R. (2023). Decoding speech perception from non-invasive brain recordings. Nature Machine Intelligence, 5(10), 1097–1107.

d’Ascoli, S., Bel, C., Rapin, J., Banville, H., Benchetrit, Y., Pallier, C., & King, J. R. (2024). Decoding individual words from non-invasive brain recordings across 723 participants. arXiv preprint.

Jayalath, D., Landau, G., Shillingford, B., Woolrich, M., & Parker Jones, O. (2025). The brain’s bitter lesson: Scaling speech decoding with self-supervised learning. ICML.

Jayalath, D., Landau, G., & Parker Jones, O. (2025). Unlocking non-invasive brain-to-text. arXiv preprint.

Moses, D. A., Metzger, S. L., Liu, J. R., Anumanchipalli, G. K., Makin, J. G., Sun, P. F., Chartier, J., Dougherty, M. E., Liu, P. M., Abrams, G. M., Tu-Chan, A., Ganguly, K., & Chang, E. F. (2021). Neuroprosthesis for decoding speech in a paralyzed person with anarthria. New England Journal of Medicine, 385(3), 217–227.

Tang, J., LeBel, A., Jain, S., & Huth, A. G. (2023). Semantic reconstruction of continuous language from non-invasive brain recordings. Nature Neuroscience, 26(5), 858–866.

Willett, F. R., Kunz, E. M., Fan, C., Avansino, D. T., Wilson, G. H., Choi, E. Y., Kamdar, F., Glasser, M. F., Hochberg, L. R., Druckmann, S., Shenoy, K. V., & Henderson, J. M. (2023). A high-performance speech neuroprosthesis. Nature, 620:1031–1036.

Citation#

Citation

Click the button below to copy the BibTeX citation:

@misc{pnpl_blog2025collaboration,

title={Building a Collaborative Foundation for Non-Invasive Speech {BCIs}: The 2025 {PNPL} Competition},

author={Elvers, Gereon and Landau, Gilad and Jayalath, Dulhan and Mantegna, Francesco and Parker Jones, Oiwi},

year={2025},

url={https://neural-processing-lab.github.io/2025-libribrain-competition/blog/building-collaborative-foundation-non-invasive-speech-bcis/},

note={Blog post}

}