Introduction#

In the 2025 PNPL Competition (Landau et al. 2025), phoneme classification is presented as a categorical problem—given neural signals, predict which of the 39 ARPABET phonemes was heard. In a previous blog, we suggested some neuroscience-inspired ideas for the speech detection task. Here, we suggest linguistics-inspired ideas for phoneme classification.

The ARPABET Phoneme Set#

Before exploring the idea of classifying phonetic features, let’s establish the complete ARPABET inventory we’re working with:

| ARPABET | IPA | Example | Type | ARPABET | IPA | Example | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | ɑ | father | vowel | L | l | lie | consonant |

| AE | æ | cat | vowel | M | m | mat | consonant |

| AH | ʌ | cut | vowel | N | n | nigh | consonant |

| AO | ɔ | caught | vowel | NG | ŋ | sing | consonant |

| AW | aʊ | cow | diphthong | OW | oʊ | boat | diphthong |

| AY | aɪ | buy | diphthong | OY | ɔɪ | boy | diphthong |

| B | b | bat | consonant | P | p | pat | consonant |

| CH | tʃ | chat | consonant | R | ɹ | rat | consonant |

| D | d | die | consonant | S | s | sat | consonant |

| DH | ð | that | consonant | SH | ʃ | shy | consonant |

| EH | ɛ | bet | vowel | T | t | tie | consonant |

| ER | ɝ | bird | vowel | TH | θ | thin | consonant |

| EY | eɪ | bay | diphthong | UH | ʊ | book | vowel |

| F | f | fat | consonant | UW | u | boot | vowel |

| G | ɡ | guy | consonant | V | v | vat | consonant |

| HH | h | hat | consonant | W | w | wise | consonant |

| IH | ɪ | bit | vowel | Y | j | yacht | consonant |

| IY | i | beat | vowel | Z | z | zap | consonant |

| JH | dʒ | jive | consonant | ZH | ʒ | pleasure | consonant |

| K | k | cat | consonant |

Total: 39 phonemes (10 vowels + 5 diphthongs + 24 consonants)

Why Phonetic Features Matter#

Phonetic features offer several compelling advantages over direct phoneme classification, particularly for MEG data where training examples may be limited:

1. Data Efficiency Through Shared Structure#

Consider these phoneme pairs and their shared features:

- /p/ and /b/: Both share [bilabial] and [stop] features, differing only in [voicing]

- /s/ and /z/: Both share [alveolar] and [fricative] features, differing only in [voicing]

- /m/ and /n/: Both share [nasal] and [voiced] features, differing only in place ([bilabial] vs [alveolar])

Instead of learning 39 independent phoneme categories, the model can learn combinations of ~30 features. This shared structure enables transfer learning—knowledge about [voicing] learned from /p/ vs /b/ pairs transfers to help distinguish /s/ vs /z/, /f/ vs /v/, and other voicing contrasts. In addition, the model is able to learn a more abstract representation of speech, structured around how the phonemes are articulated in the mouth, which could also benefit the classification of other phonemes such as those not in the English language without further training data.

2. Handling Low-Frequency Phonemes#

Some phonemes occur infrequently in speech corpora. Looking at the actual distribution from the LibriBrain dataset (Özdogan et al. 2025), phoneme frequencies vary dramatically:

High-frequency phonemes:

- AH /ʌ/ (~11%): most common vowel

- N /n/ (~7%): frequent nasal consonant

- T /t/ (~6%): common stop consonant

Low-frequency phonemes:

- NG /ŋ/ (~1%): appears in “sing”, “thing”

- ZH /ʒ/ (~0.2%): appears in “pleasure”, “vision”

- OY /ɔɪ/ (~0.1%): appears in “boy”, “coin”

Direct classification might struggle with limited training data for rare phonemes, but feature-based approaches can leverage shared structure. For /ŋ/, the model can use:

- [nasal] feature: learned from frequent /m/ (~2%) and /n/ (~7%)

- [velar] feature: learned from frequent /k/ (~3%) and /g/ (~1%)

- [voiced] feature: learned from many voiced phonemes

The model can then recognise /ŋ/ as the intersection of [nasal] + [velar] + [voiced], even with limited direct /ŋ/ examples.

3. Biological Plausibility#

Neurophysiological evidence suggests the brain may encode speech in terms of articulatory features rather than whole phonemes (e.g. Mesgarani et al. 2014). MEG signals might naturally align with feature-based representations, potentially improving classification accuracy.

4. Graceful Degradation#

When predictions are uncertain, feature-based models provide partial information. Instead of a completely wrong phoneme prediction, you might get the correct manner of articulation ([fricative]) even if the place of articulation ([alveolar] vs [postalveolar]) is incorrect.

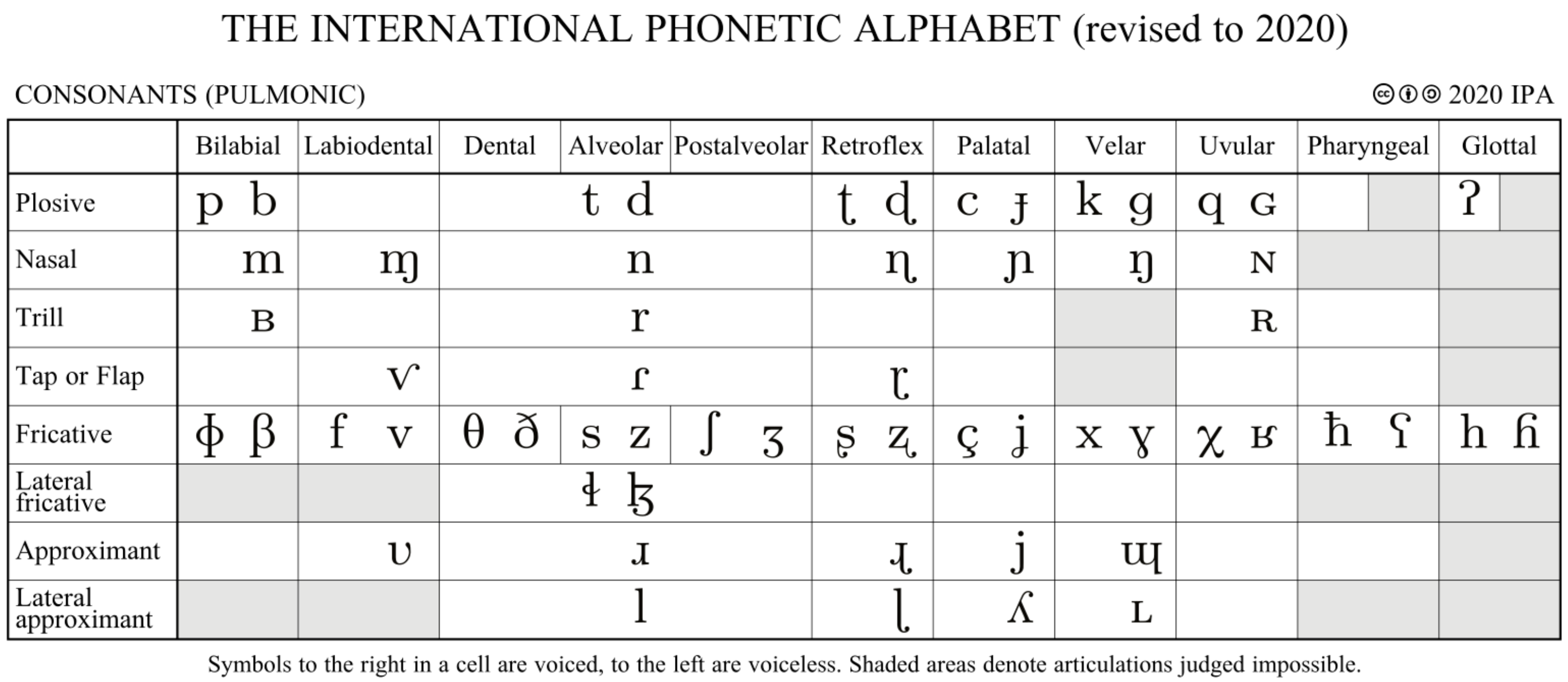

Universal Phonetic Features: The IPA Foundation#

The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) provides a systematic framework for describing speech sounds based on how they are articulated.

Figure: The IPA consonant chart shows all known and even possible consonants in human languages produced with air from the lungs (from Wikipedia, accessed 21 September 2025)

Consonant Features#

For the 24 consonants in English, we can define features based on three primary dimensions:

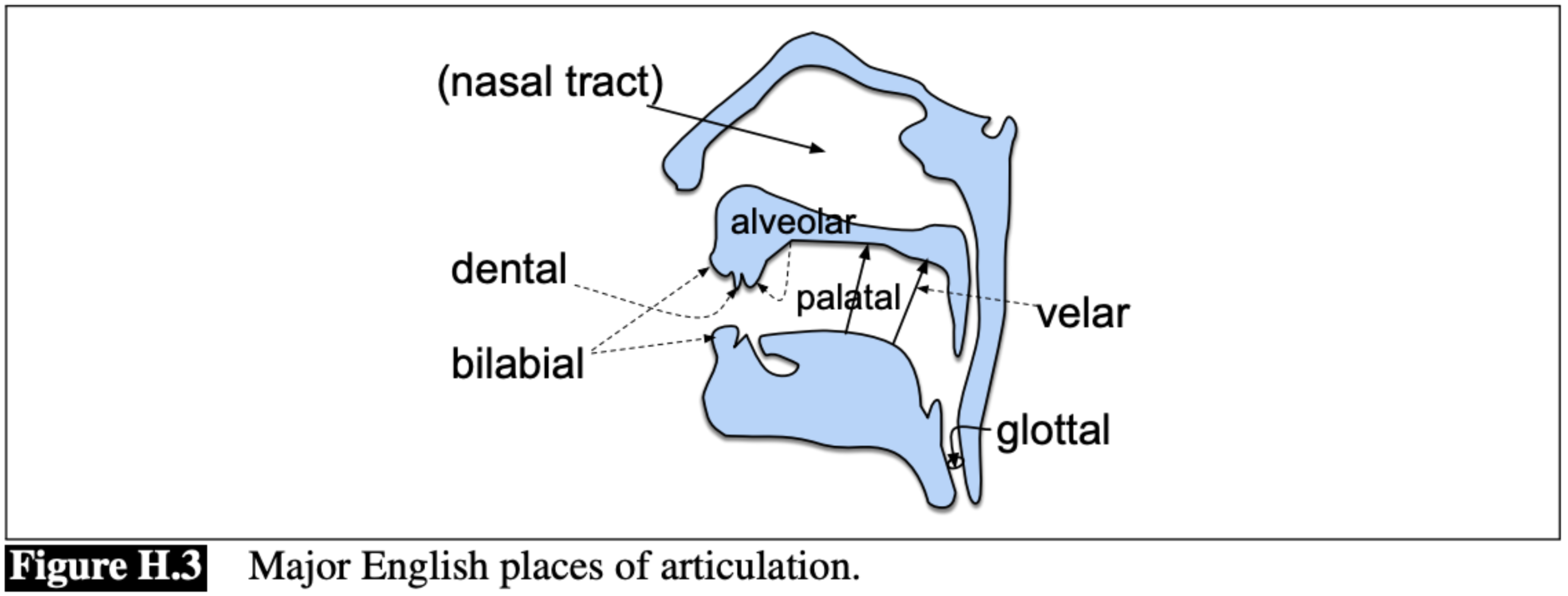

Place of Articulation

- Bilabial: /p, b, m/ - sounds made with both lips

- Labiodental: /f, v/ - sounds made with lip and teeth

- Dental: /θ, ð/ - sounds made with tongue and teeth

- Alveolar: /t, d, s, z, n, l, ɹ/ - sounds made at the alveolar ridge

- Post-alveolar: /ʃ, ʒ, tʃ, dʒ/ - sounds made behind the alveolar ridge

- Palatal: /j/ - sounds made with the middle or back part of the tongue raised to the hard palate

- Labial-velar: /w/ - sounds made with the back part of the tongue raised toward the soft palate while rounding the lips

- Velar: /k, g, ŋ/ - sounds made at the soft palate

- Glottal: /h/ - sounds made at the glottis

Figure: A sagittal view of the vocal articulators and major places of articulation used in English (from Jurafsky and Martin 2025, accessed 21 September 2025)

Manner of Articulation

- Plosive: /p, b, t, d, k, g/ - complete obstruction of airflow

- Fricative: /f, v, θ, ð, s, z, ʃ, ʒ, h/ - partial obstruction creating friction

- Affricate: /tʃ, dʒ/ - sequential combination of plosive and then fricative

- Nasal: /m, n, ŋ/ - airflow through the nose

- Liquid: /l, ɹ/ - airflow around or over the tongue

- Glide: /w, j/ - vowel-like consonants

Voicing

- Voiced: vocal cords vibrate during production

- Voiceless: no vocal cord vibration

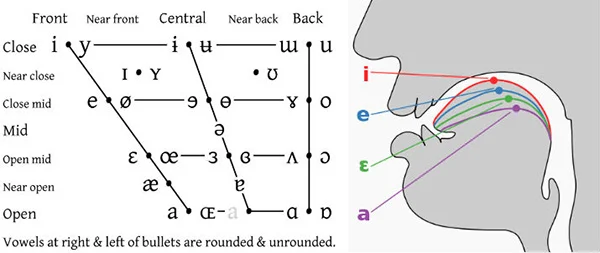

Vowel Features#

For the 10 vowels, the core IPA features include:

- Height: close, near-close, close-mid, mid, open-mid, near-open, open (7 levels)

- Backness: front, near-front, central, near-back, back (5 levels)

- Roundedness: rounded, unrounded

This finer-grained system that specifies multiple degrees of height, for example, allows us to distinguish vowel pairs like /ɪ/ (near-close near-front unrounded) vs /i/ (close front unrounded), or /ʊ/ (near-close near-back rounded) vs /u/ (close back rounded). Note that front/back and close/open correspond roughly to tongue positions in the mouth (close/open also corresponds to how open the jaw is); roundedness relates to the lips.

Figure: Positions in the IPA vowel chart correspond to tongue position (from blog, accessed 21 September 2025)

Diphthong Features#

For diphthongs, ARPABET uses the following digraphs (AY, AW, EY, OY, OW). Diphthongs can be approximated by a sequence of two other IPA symbols for the English monophthong vowels, each with their own articulatory features:

- AY /aɪ/ → /ɑ/ + /ɪ/ (open back unrounded + near-close near-front unrounded)

- AW /aʊ/ → /ɑ/ + /ʊ/ (open back unrounded + near-close near-back rounded)

- EY /eɪ/ → /ɛ/ + /ɪ/ (open-mid front unrounded + near-close near-front unrounded)

- OW /oʊ/ → /ɔ/ + /ʊ/ (open-mid back rounded + near-close near-back rounded)

- OY /ɔɪ/ → /ɔ/ + /ɪ/ (open-mid back rounded + near-close near-front unrounded)

These differ from English monophthongs like IH /ɪ/, which map to single IPA symbols with their own features.

Incidentally, some analyses of English vowels prefer features like tenseness (tense vs lax) to distinguish vowels like /i/, /o/, /u/ from /ɪ/, /ɔ/, /ʊ/. This is not an IPA feature but rather represents a language-specific categorisation that correlates in the IPA with the more precise height and backness distinctions above.

Complete IPA-Based Feature Set for ARPABET#

Here’s a template binary feature matrix for the ARPABET phonemes:

Consonants#

| Phoneme | Bilabial | Labiodental | Dental | Alveolar | Post-alveolar | Palatal | Labial-velar | Velar | Glottal | Plosive | Fricative | Affricate | Nasal | Liquid | Glide | Voiced |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /p/ | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| /b/ | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| /t/ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| /d/ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| /k/ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| /g/ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| /f/ | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| /v/ | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| /θ/ | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| /ð/ | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| /s/ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| /z/ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| /ʃ/ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| /ʒ/ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| /h/ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| /tʃ/ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| /dʒ/ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| /m/ | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| /n/ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| /ŋ/ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| /l/ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| /r/ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| /w/ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| /j/ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

Vowels (Monophthongs)#

| Phoneme | Close | Near-close | Close-mid | Mid | Open-mid | Near-open | Open | Front | Near-front | Central | Near-back | Back | Rounded |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /ɑ/ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| /æ/ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| /ʌ/ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| /ɔ/ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| /ɛ/ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| /ɝ/ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| /ɪ/ | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| /i/ | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| /ʊ/ | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| /u/ | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

Here we assume that diphthongs are split into separate monophthongs (e.g. /ɔɪ/ → /ɔ/ + /ɪ/).

This means that there are no separate entries for diphthongs which solves the problem of how to assign features like [rounded] to a diphthong like /ɔɪ/ (i.e. /ɔ/ is [+rounded] and /ɪ/ is [−rounded]).

Note that affricates like /dʒ/ could also be separated into simpler phonemes (/d/ and /ʒ/), but the same difficulty with assigning features to them does not arise.

Alternative Feature Sets#

While IPA-based features provide a solid foundation based on articulatory features, it is not the only option. For example, sets that mix articulatory features (as in the IPA) with other kinds of features can be seen in prior studies of the brain.

Mixed Feature Sets in Neuroscience#

The influential work by Mesgarani et al. (2014) used surgical cortical recordings from human superior temporal gyrus (STG) during natural speech listening to demonstrate that individual brain sites show selectivity to distinct phonetic features rather than whole phonemes. Their study used a mixed feature set combining the following:

- Articulatory features: manner of articulation (e.g. plosive, fricative, nasal), place of articulation (e.g. bilabial, alveolar, velar), voicing (primarily for consonants)

- Acoustic parameters: voice onset time (VOT) for distinguishing voiced/voiceless plosives; fundamental frequency (F0) and formant frequencies (F1-F4) for vowel classification

- Perceptual groupings: obstruent vs sonorant categories (obstruents include stops, fricatives, and affricates - sounds with significant constriction; sonorants include vowels, nasals, liquids, and glides - sounds with relatively open vocal tract and greater acoustic energy)

With this combination of feature sets, they found that:

- STG electrodes showed hierarchical organisation: first dividing between obstruent-selective and sonorant-selective sites, then subdividing by manner of articulation (plosives vs fricatives) and vowel categories (low-back, low-front, high-front vowels, nasals)

- Selectivity was organised primarily by manner of articulation and secondarily by place of articulation, corresponding to acoustic spectrotemporal properties

- Individual electrodes showed nonlinear encoding of acoustic parameters like VOT, suggesting specialised mechanisms for categorical speech perception

One of the limitations, however, with the Mesgarani study was that they used an incomplete set of 14 phonetic features that do not distinguish all English phonemes. To be clear, 14 binary features could be enough to distinguish 39 phonemes, as we explain below. But the choice of specific features used in the study does not end up separating all phonemes. So additional features would be needed to produce a complete classification system - though as we note near the conclusion, there are probably benefits even for the use of partial feature sets.

The Mathematics of Feature Space#

How many binary features do we need to uniquely represent n phonemes? The theoretical minimum follows from information theory:

Minimum features needed: ⌈log₂(n)⌉

For 39 ARPABET phonemes: ⌈log₂(39)⌉ = ⌈5.29⌉ = 6 binary features

However, this assumes optimal encoding. Linguistically-motivated features typically require more dimensions for interpretability and biological plausibility.

Why Binary Features?#

By convention, linguists often encode phonetic properties as binary features (present=1, absent=0). Features like [±voiced] or [±nasal] naturally divide phonemes into two groups. From a machine learning perspective, binary features also allow us to perform binary classification, which has numerous benefits including simplifying the hypothesis space for the model, making training more efficient and inference more robust, and avoiding the need to impose arbitrary ordinal relationships between categories.

Handling Gradient Properties: Some phonetic dimensions (especially vowel height and backness) exist on continua rather than discrete categories. For monophthongs, we handle this by:

- Discretising the continuum: Instead of one “height” feature, we use multiple binary features (close, near-close, close-mid, mid, open-mid, near-open, open)

- Exclusive categories: Each vowel gets exactly one height feature and one backness feature

For example, with the vowel phoneme IY /i/, we can attribute the following features, where the seven height positions capture the vowel space from highest tongue position (close) to lowest (open), while the five backness positions capture front-to-back tongue placement:

- Height: [1,0,0,0,0,0,0] to correspond to “close”

- Backness: [1,0,0,0,0] to correspond to “front”

With the phoneme IH /ɪ/, we can attribute the following features:

- Height: [0,1,0,0,0,0,0] to correspond to “near-close”

- Backness: [0,1,0,0,0] to correspond to “near-front”

The rest of the vowel phoneme features can be assigned in a similar way. The full feature attribution can be seen above in the full IPA-based binary feature matrix.

Diphthong Challenge#

Diphthongs like /aɪ/ move between two vowel targets, making single feature assignment problematic. We present here several ways to model diphthongs with their pros and cons:

Approach 1: Decomposition

We can treat each diphthong as a sequence of two monophthong feature vectors:

- AW /aʊ/ → two vectors: /ɑ/ [open, back, unrounded] + /ʊ/ [near-close, near-back, rounded]

- AY /aɪ/ → two vectors: /ɑ/ [open, back, unrounded] + /ɪ/ [near-close, near-front, unrounded]

Pros: Preserves temporal sequence, uses consistent monophthong features

Cons: Doubles the sequence length, requires temporal modelling

Approach 2: Blended Features

We can set multiple features to represent the vowel space covered:

- AY /aɪ/: height=[open, near-close], backness=[back, near-front], rounding=[unrounded]

- AW /aʊ/: height=[open, near-close], backness=[back, near-back], rounding=[unrounded, rounded]

Pros: Single vector per diphthong, compact representation

Cons: Loses temporal information, creates ambiguous feature combinations

Approach 3: Phonological Features

We can use higher-level (more abstract) phonological distinctions. For example, we can have the binary features [diphthong], [front-gliding], [back-gliding], [height-changing] to represent each diphthong according to its vowel transition:

- AY /aɪ/: [diphthong=1, front-gliding=1, height-changing=1]

- AW /aʊ/: [diphthong=1, back-gliding=1, height-changing=1]

Pros: Captures diphthong-specific properties, linguistically motivated

Cons: Requires domain knowledge, may miss low-level articulatory details

Brute Force Feature Discovery#

Since the “correct” feature set for neural representation is unknown, we can systematically search the feature space:

Approach 1: Exhaustive Binary Search#

For k binary features representing n phonemes, we have a total of 2^(n×k) possible feature assignments. With the constraint that each phoneme must have a unique feature vector (i.e. considering only assignments where each of the n assigned feature vectors are distinct from each other), we can train a classifier to map MEG data to the assigned binary features and measure how accurately it predicts the binary features from the neural input. The set of binary feature vectors with the highest model accuracy would be the best set to use. However, although this approach is tractable for small k, it grows exponentially which may be computationally infeasible for larger k.

Approach 2: Evolutionary Search#

A similar but less exhaustive approach involves modifying the best-performing feature sets and evaluating model performance on the mutated feature sets. The following steps can be taken for the evolutionary search approach:

- Initialise random population of feature sets

- Evaluate each set by training classifier on MEG data

- Select best-performing feature sets

- Apply mutation/crossover to generate new candidates

- Repeat until convergence

General Implementation Strategy#

Here, we provide some general implementation tips which could help with the development of robust and accurate models for phoneme classification.

- Start Simple: Begin with established phonetic features (e.g. IPA-based)

- Establish Baseline: Compare feature-based classification against direct phoneme classification

- Analyse Error Patterns: Use confusion matrices to identify systematic classification errors

- Feature-grouped analysis: Group phonemes by shared features (e.g. all fricatives, all front vowels) to see if errors cluster within feature categories

- Feature-specific errors: Examine whether errors primarily involve voicing confusions ([p/b], [t/d], [k/g]), place confusions ([p/t/k], [b/d/g]), or manner confusions ([p/f], [b/v])

- Cross-feature patterns: Look for errors that cross feature boundaries (vowel/consonant confusions, which might indicate fundamental encoding differences)

- Expand Systematically: Add features incrementally, measuring impact on performance and error reduction

- Search Strategically: Use evolutionary or gradient methods to discover novel feature combinations

- Validate Interpretability: Ensure discovered features have linguistic or neurobiological interpretation

Practical Implementation for the Competition#

The competition task requires mapping from brain data to probability distributions over all 39 ARPABET phonemes. However, you can implement feature-based classification internally while still meeting this requirement through conversion:

Feature-to-Phoneme Conversion Pipeline#

- Train feature classifiers: Build separate binary classifiers for each phonetic feature (e.g. [voiced], [fricative], [front])

- Predict feature probabilities: For each input, obtain probability estimates for all features

- Convert to phoneme probabilities: Map feature combinations back to phoneme probabilities using either:

- Distance-based mapping: Calculate similarity between predicted features and known phoneme feature vectors

- Learned mapping: Train a secondary classifier to map from feature space to phoneme space

- Probabilistic matching: Use Bayesian inference to compute P(phoneme|features)

Example Conversion Methods#

Distance-based approach:

| |

Probabilistic approach:

| |

Incremental Strategy#

Since conversion back to phonemes is always possible, you don’t need a complete feature set:

- Start with consonants only: Implement features for the 24 consonants (manner, place, voicing), use direct classification for vowels/diphthongs

- Add vowel subsets: Gradually incorporate vowel features (height, backness, rounding) as you refine the approach

- Handle diphthongs last: These are the most complex; initially treat them as single units or use simplified approximations

Potential Benefits of Partial Feature Implementation#

- Reduced complexity: Focus on phoneme classes where features are most clear-cut (consonants)

- Faster iteration: Test feature-based approaches without solving all edge cases upfront

- Graceful degradation: Even partial feature success should improve overall classification

- Modular development: Different team members can work on different feature types independently

The measure of success is that any improvement in feature-based classification translates to better phoneme predictions after conversion, making this a practical approach to investigate even with incomplete feature sets.

Conclusion#

Phonetic features offer a principled way to decompose the phoneme classification problem while potentially revealing insights about how the brain processes speech. Whether using established linguistic features or discovering new ones through systematic search, this approach opens new avenues for understanding the neural basis of speech perception.

The competition provides an ideal testbed for exploring these ideas. We encourage participants to move beyond direct phoneme classification and explore the rich structure that phonetic features can provide.

References#

Gwilliams, L., King, J. R., Marantz, A. & Poeppel, D. (2022). Neural dynamics of phoneme sequences reveal position-invariant code for content and order. Nat Commun 13, 6606 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-34326-1

Mesgarani N., Cheung C., Johnson K., & Chang E. F. (2014). Phonetic feature encoding in human superior temporal gyrus. Science. 343(6174):1006-10. doi: 10.1126/science.1245994. PMID: 24482117; PMCID: PMC4350233.

Jayalath, D., Landau, G., Shillingford, B., Woolrich, M., & Parker Jones, O. (2025). The Brain’s Bitter Lesson: Scaling Speech Decoding With Self-Supervised Learning. ICML. https://icml.cc/virtual/2025/poster/44019

Previous Blog Posts on the 2025 PNPL Competition

Mantegna, F., Elvers, G., & Parker Jones, O. (2025). Brain-Inspired Approaches to Speech Detection [Blog post]. https://neural-processing-lab.github.io/2025-libribrain-competition/blog/brain-inspired-approaches-speech-detection

Landau, G., Elvers, G., Özdogan, M. & Parker Jones, O. (2025). The Speech Detection task and the reference model [Blog post]. https://neural-processing-lab.github.io/2025-libribrain-competition/blog/speech-detection-reference-model

The 2025 PNPL Competition and LibriBrain dataset

Landau, G., Özdogan, M., Elvers, G., Mantegna, F., Somaiya, P., Jayalath, D., Kurth, L., Kwon, T., Shillingford, B., Farquhar, G., Jiang, M., Jerbi, K., Abdelhedi, H., Mantilla Ramos, Y., Gulcehre, C., Woolrich, M., Voets, N., & Parker Jones, O. (2025). The 2025 PNPL Competition: Speech Detection and Phoneme Classification in the LibriBrain Dataset. NeurIPS, Competition Track. https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.10165

Özdogan, M., Landau, G., Elvers, G., Jayalath, D., Somaiya, P., Mantegna, F., Woolrich, M., & Parker Jones, O. (2025). LibriBrain: Over 50 Hours of Within-Subject MEG to Improve Speech Decoding Methods at Scale. NeurIPS, Datasets & Benchmarks Track. https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.02098

Citation#

Citation

Click the button below to copy the BibTeX citation:

@misc{pnpl_blog2025phoneme_ideas,

title={Language-Inspired Approaches to Phoneme Classification},

author={Kwon, Teyun and Cho, SungJun and Elvers, Gereon and Mantegna, Francesco and Parker Jones, Oiwi},

year={2025},

url={https://neural-processing-lab.github.io/2025-libribrain-competition/blog/language-inspired-approaches-phoneme-classification},

note={Blog post}

}