The Speech Detection Task and the Reference Model

Exploring the Speech Detection task and the reference model architecture used in the LibriBrain competition, including insights into our 'Start Simple' approach and future research directions.

Note: This blog post was originally published on the LibriBrain Competition website and is reproduced here with permission.

Introduction

The remarkable progress of Deep Learning in the past decade follows a recurrent motif: define a clear task (e.g., image classification), assemble a large, relevant dataset (e.g., ImageNet), and apply cutting-edge architectures (e.g., AlexNet). At PNPL, we believe that decoding speech directly from the brain is the next great frontier for deep learning. Inspired by past successes, we adopted a similar structured approach. We first established clear, scalable tasks, collected the necessary data, and are now employing state-of-the-art methods while inviting the wider research community to collaborate.

Starting Simple

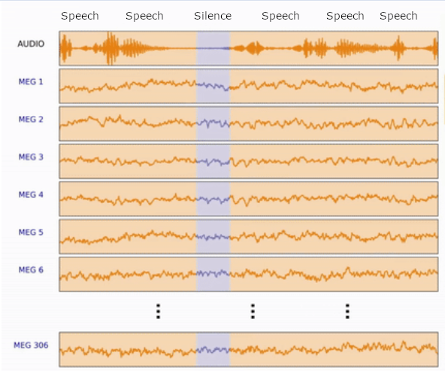

Based on our "Start Simple" approach, we decided to begin with a fundamental speech decoding task: Speech Detection. This task is analogous to the "Speech Detection" task from the audio analysis domain - it involves labelling segments of brain signals as either "Speech" or "Non Speech," depending on whether speech stimuli were presented during that period.

Figure 1 - MEG with Speech/Silence labels

Figure 1 - MEG with Speech/Silence labels

From Sequence-to-Sequence to Simplified Classification

A natural way to frame the Speech Detection task is as a sequence-to-sequence task: with brain signal as input and a sequence of "Speech/Non-Speech" labels as output. Seq2Seq learning uses an "Encoder-Decoder" architecture, in which the input sequences are encoded into a vector and then decoded back to a new sequence with varying length and dimensions. The Seq2Seq architecture family was found to be very useful for tasks such as Machine Translation in which the input sequence and the output sequence have differing lengths and dimensionality. While the original Seq2Seq model was based on LSTM architecture it was later replaced with the ubiquitous Transformer block.

Figure 2 - Speech Detection as Seq2Seq task

Figure 2 - Speech Detection as Seq2Seq task

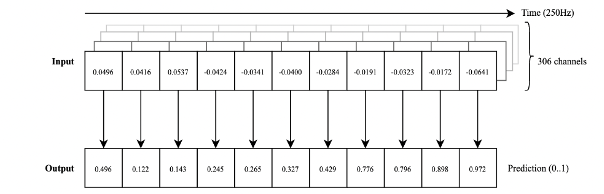

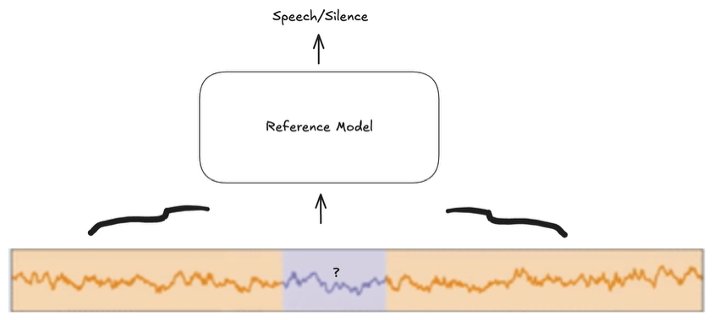

Our Simplified Approach

We made a decision not to utilize Seq2Seq architecture and opted for a simpler approach. Instead of processing the entire sequence, our reference model analyzes a fixed-length segment of MEG data and classifies a single central sample point as either speech or silence. We chose a segment length of 200 samples, compatible with the sequence length limitation of the LSTM block used for the temporal pooling. The model was set up as a binary classifier whose target is "Speech/No Speech" label for the middle sample. Choosing the middle sample as a target maximized the amount of information for prediction, as the model can use both the preceding and succeeding samples to arrive at a decision. Structuring the model this way simplified and reduced the original task significantly, making it easier to train and optimize with a small number of parameters.

Figure 3 - Reference Model binary classification of middle sample

Figure 3 - Reference Model binary classification of middle sample

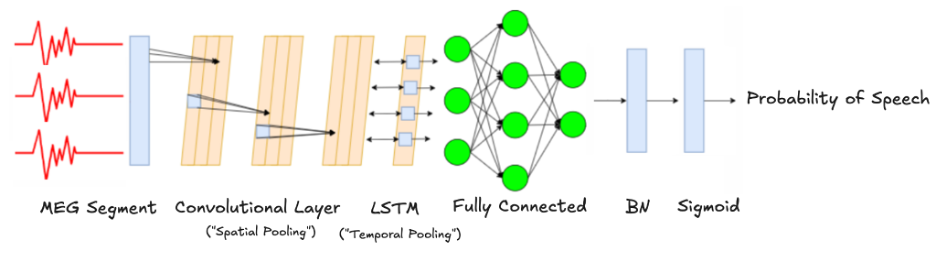

Model Architecture

We chose a simple and intuitive architecture combining Convolutional and LSTM layers. The convolutional layer performs "Spatial Pooling" across MEG sensors, while the LSTM handles "Temporal Pooling" over time samples. Spatial Pooling is the aggregation of information from all the sensors that receive information from different spatial locations in the brain, while Temporal Pooling is the aggregation of the sensor's information over time. We implemented the "Spatial Pooling" with 1d convolution over the sequence of sensors. We carried out an architectural search and hyperparameter tuning and arrived at a compact and effective architecture which significantly outperforms baseline, with relatively few parameters.

Figure 4 - Model Architecture

Figure 4 - Model Architecture

Dataset Imbalance Challenges

The experiment design for our MEG recording sessions is composed mostly of "Speech" segments, making "Silence" periods comparatively rare. We designed the experiment this way so as to optimize the recording time for a variety of different speech decoding tasks. Nevertheless, there is still an open question as to how to design an experiment for optimizing Speech/Non-Speech detection. It is also worth noting that Non-Speech is an open-ended term, because there could be infinite variability of the Non-Speech stimuli. We hope to tackle this issue more rigorously in the future.

Given the unbalanced Speech to Non-Speech dataset, we adjusted our sampling strategy to focus more closely on the less frequent silent intervals. Specifically, we used smaller sampling strides when moving through silent segments (a method we call "jittering"), giving the model frequent exposure to these rare events, while using larger strides for the speech segments. This approach helped ensure balanced training and improved model sensitivity and accuracy.

Incorporating Neuroscientific Insights

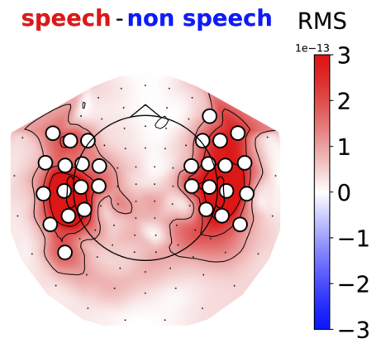

Further simplification was made possible by incorporating neuroscientific insights. Analysis of MEG data revealed that the most critical signal for speech detections lies predominantly in the brain's temporal lobes, results that are well corroborated by the neuroscientific literature (Hamilton et al., 2018). By selectively focusing on these informative sensors and masking others, we significantly reduced model complexity and improved training stability.

Figure 5 - Temporal Areas MEG Sensors are highly indicative of speech segments

Figure 5 - Temporal Areas MEG Sensors are highly indicative of speech segments

Looking Forward

Decoding speech from brain signals is a challenging task that, until recently, has been explored primarily by neuroscientists. Yet, we firmly believe that by making the speech decoding domain more standardised and accessible, we will encourage greater involvement from the research community, leading to progressively better methods and benchmarks. Our "Start Simple" strategy aims to spark interest and accelerate progress, making Speech Decoding tasks into the next Deep Learning success story.

Since very happy to have you join on the fun, we would like to share with you some of our future research directions for the Speech Detection task:

- Incorporating Transformer models (they seem to win at every task that involves sequence analysis)

- Adding an Auto-Regressive head for contextual information

- Using a Whisper-like model as a backbone

- Modelling Speech as a "One-Class Classification", with Non-Speech based on distance from Speech.

- Adding synthetic data for both speech and non-speech.

- Spatially-conscious 2D/3D convolution, based on the actual sensors' spatial coordinates.

With all that in mind, the best way for you to get started is by having a look at the Speech Detection tutorial notebook, which can be found on our "Participate" page here.

📄Cite this blog post

Use this citation format to reference this blog post in your research

@misc{pnpl_blog2025speechDetectionReference,

title={The Speech Detection task and the reference model},

author={Landau, Gilad and Elvers, Gereon and Özdogan, Miran and Parker Jones, Oiwi},

year={2025},

url={https://neural-processing-lab.github.io/2025-libribrain-competition/blog/speech-detection-reference-model},

note={Blog post}

}References

The 2025 PNPL Competition: Speech Detection and Phoneme Classification in the LibriBrain Dataset

Gilad Landau, Miran Özdogan, Gereon Elvers, Francesco Mantegna, Pranav Somaiya, Dulhan Jayalath, Lukas Kurth, Taewon Kwon, Brendan Shillingford, Gabriel Farquhar, Michael Jiang, Karim Jerbi, Hichem Abdelhedi, Yorguin Mantilla Ramos, Caglar Gulcehre, Mark Woolrich, Natalie Voets, Oiwi Parker Jones

LibriBrain: Over 50 Hours of Within-Subject MEG to Improve Speech Decoding Methods at Scale

Miran Özdogan, Gilad Landau, Gereon Elvers, Dulhan Jayalath, Pranav Somaiya, Francesco Mantegna, Mark Woolrich, Oiwi Parker Jones

Sequence to sequence learning with neural networks

Ilya Sutskever, Oriol Vinyals, Quoc V. Le

ImageNet: A Large-Scale Hierarchical Image Database

Jia Deng, Wei Dong, Richard Socher, Li-Jia Li, Kai Li, Li Fei-Fei

ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks

Alex Krizhevsky, Ilya Sutskever, Geoffrey E. Hinton

Attention is all you need

Ashish Vaswani, Noam Shazeer, Niki Parmar, Jakob Uszkoreit, Llion Jones, Aidan N. Gomez, Lukasz Kaiser, Illia Polosukhin

A Spatial Map of Onset and Sustained Responses to Speech in the Human Superior Temporal Gyrus

Liberty S. Hamilton, Erik Edwards, Edward F. Chang